NHD Paediatric Hub

Dietary treatment in Crohn’s disease

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a chronic condition which is characterised by patchy, transmural inflammation that can affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract from mouth to anus. It is a lifelong condition with periods of remission or relapse. The incidence of paediatric CD is rising, with a mean age at diagnosis of 11.9 years.(1) 25-30% of patients with CD are diagnosed by the age of 20.

Patients with CD within the paediatric setting present with a variety of symptoms. Abdominal pain is usually prominent, alongside persistent loose stools/diarrhoea with or without blood. Other reported symptoms include nocturnal stooling, tenesmus, lethargy, anorexia, nausea, growth delay and delayed puberty. Diagnosis is often associated with poor growth and undernutrition, and dietitians are key in the management of this patient group.(2,3)

Diet therapies play a key role in the treatment of the young person with CD.(2, 3) Exclusive enteral nutrition (EEN) is recommended as first-line treatment for the majority of paediatric patients at time of diagnosis to induce remission. EEN will also be used as a preoperative management for patients undergoing surgery linked to their CD.(2, 3)

The main aim of treatment is symptom relief, growth and pubertal development (depending on age at diagnosis/flare). By successfully managing symptoms, this in turn will lead to reducing complications and improving quality of life.

EVIDENCE FOR US OF EEN IN CD

EEN is a nutritional therapy used for inducing remission in CD and is now widely recognised as the first-line treatment for active CD2 (3) - for the induction of remission at diagnosis and for periods of flare. EEN has many clear benefits and has been shown to improve nutritional complications, improve weight loss and inflammatory markers and promote mucosal healing. It was demonstrated to be as effective at inducing remission as corticosteroids.(4,5) EEN also has the added benefit of minimal side effects.

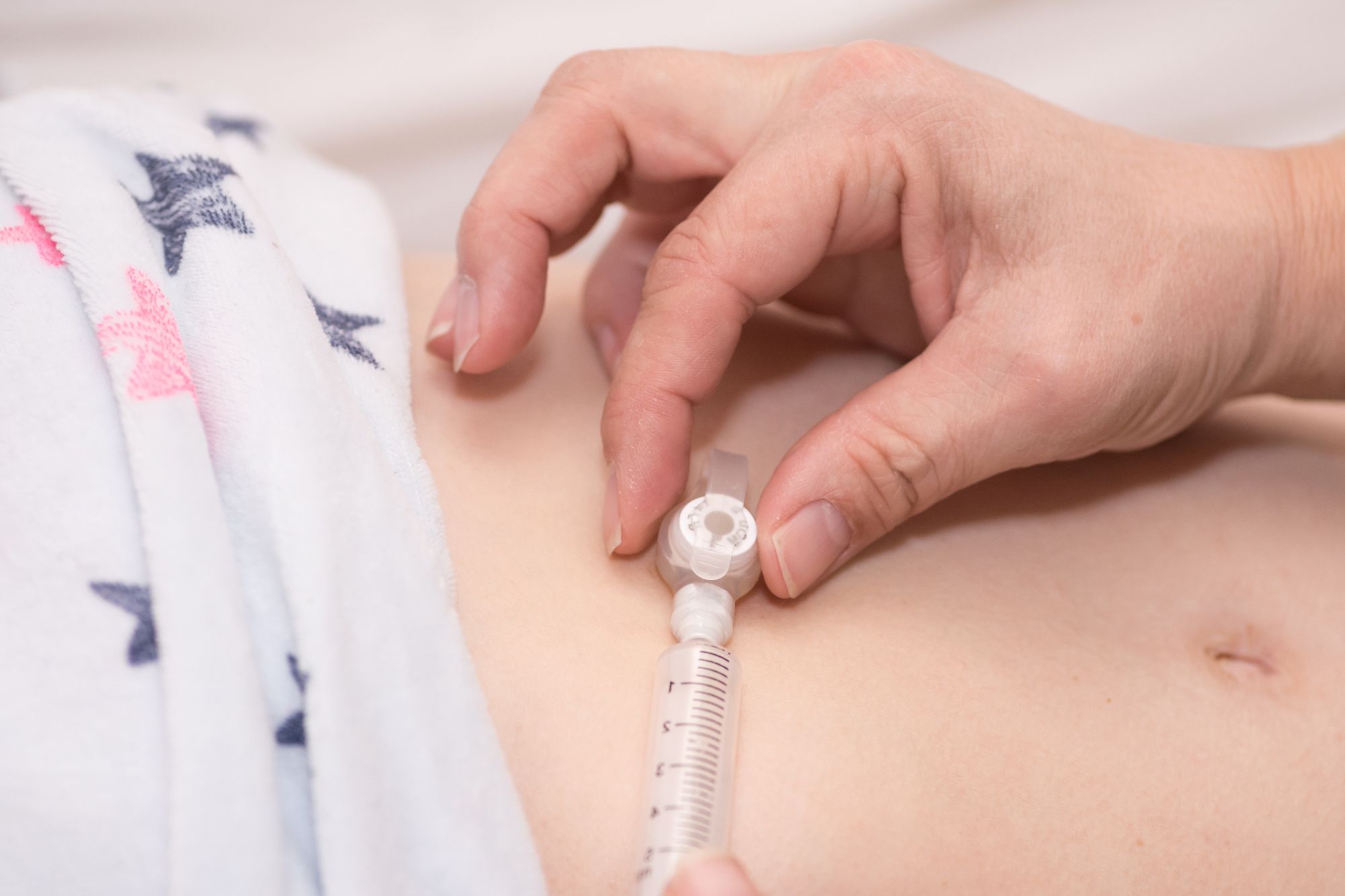

EEN usually consists of six to eight weeks of exclusive liquid diet as a sole source of nutrition. Full nutritional requirements are provided by the liquid formulation and, therefore, patients should not feel hungry once tolerating full volumes. The majority of patients are able to tolerate EEN orally.(2,3,6) EEN can be based on a polymeric feed (whole protein) or an elemental feed (which should only be used in cases of pre-existing milk allergy).

The efficacy of EEN is not fully understood but there is ongoing research to try to establish how and why it works. It is believed to enhance changes to the gut microbiota, reduce intestinal permeability, enhance the protection of the intestinal barrier and lessen the impact of pro-inflammatory cytokines – this in turn leads to gut healing and symptom improvement in paediatric CD patients.(5)

Although current guidelines recommend EEN as being the first-line treatment for achieving remission for children with CD, there is growing interest regarding other strategies that may help achieve remission whilst improving quality of life.

PARTIAL ENTERAL NUTRITION (PEN)

PEN is the term used to describe a proportion of requirements from enteral feeds alongside eating a normal varied diet. ESPGHAN does not recommend partial enteral nutrition for induction of remission. However, this recommendation is based on the finding of a single RCT. A more recent study by Lee et al in 2015(7) concluded that 50% of patients on PEN achieved remission when using it as induction therapy.

The volume of PEN appears to be fundamental to ensuring therapeutic levels are achieved: it is currently recommended that PEN provides >50% of energy requirements. This has a significant impact on appetite and quality of life and is felt to be unsustainable in the long term. Another point to consider when prescribing PEN as a maintenance strategy is that you may be asking patients to complete a further course of EEN and if taking large volumes of PEN they may not be able to take adequate volumes for EEN.

Once remission has been achieved, PEN can be used to help prolong periods between relapses as part of maintenance therapy. ESPGHAN and ECCO now recommend that PEN may be used as maintenance therapy alongside other medications (eg, immunomodulators).(2,3)

CROHN'S DISEASE EXCLUSION DIET

Crohn’s disease exclusion diet (CDED) is a whole food diet coupled with partial enteral nutrition. The diet limits animal fat, certain types of meat, gluten, maltodextrin, emulsifiers, sulphites and certain monosaccharides.(9) Research showed that PEN provided 50% of calculated energy requirements alongside CDED diet for a period of six weeks, followed by a step-down period where PEN provided 25% of nutritional requirements alongside CDED. Clinical remission was achieved in 80% of patients following both PEN and CDED.(9) There is questionability over the need for PEN alongside CDED diet to sustain remission rates. However, it is well recognised that PEN contributes to calorie intake, as well as calcium intake which is essential in improving nutritional benefit whilst on this dietary treatment. The diet is complicated, avoiding a large number of foods, which may make achieving it with families outside of the supportive research environment difficult.

CD TREATMENT WITH EATING DIET (CD-TREAT)

CD-TREAT is a solid food-based diet that recreates the composition of EEN (Modulen IBDTM, Nestle). The diet excludes dietary components like gluten and lactose and matches other nutrient profiles such as carbohydrates and proteins.(10) CD-TREAT aims to mimic EEN's effect on the gut microbiome, metabolome, inflammation and clinical outcomes.

In an RCT by Svolos et al from 2019 (10), CD-TREAT was used as an induction therapy in five paediatric patients who had active CD. The patients were provided with CD-TREAT meals and snacks, which they selected from a menu. They followed the CD-TREAT diet for a period of eight weeks. 80% (4/5) children had a clinical response with 3/5 achieving remission with a significant decrease in faecal calprotectin. This research also analysed the impact of CD-TREAT on healthy adults and rat models. The researchers reported that CD-TREAT was more acceptable to adults than EEN and reported positive changes in stooling microbiome and metabolome.

Whilst the evidence suggests the CD-TREAT diet has good outcomes by replicating EEN changes in the microbiome and decreasing gut inflammation, the diet may be difficult to follow out with research protocols when families have to plan and make their own meals.

SPECIFIC CARBOHYDRATE DIET (SCD)

SCDs eliminate all grains, sugar (except for honey), all milk products (except hard cheese and yoghurt fermented more than 24 hours) and most processed foods.(8) An RCT by Suskind et al from 2020 split patients into three subcategories following SCD.(8) Patients were randomised to either full SCD, modified SCD (SCD diet but including oats and rice) or whole foods diet which excluded wheat, corn, sugar, milk and food additives. The diet was followed for 12 weeks. The sample size was small. All patients who completed the 12 weeks of dietary therapy achieved remission; however, there was variation within inflammatory markers with the more exclusionary diets being associated with a better resolution of inflammation (eg, CRP/ESR markers). Whilst the sample size was small, this study provides useful information in further learning about the impact of the foods we eat on gut microbiota.

The SCD is complex and some families may find the diet plans difficult to follow, Further research is needed prior to introduction in clinical practice.

CONCLUSION

EEN remains the main dietary treatment for induction of remission in paediatric CD. The evidence suggests it is well tolerated, achievable and has good response rates. The role of diet within both the induction and maintenance of remission of paediatric CD is an area that has gained substantial interest and research over recent years and is one that is likely to change and continue to develop. EEN is well established as an induction treatment within the paediatric population and its use within adult CD patients is now being considered.

The role of PEN for induction as well as maintenance of remission is now being considered as are many variants of dietary therapies, of which the key ones are mentioned above. Patients with CD are at nutritional risk with concerns around growth, malnutrition, anorexia and bone health and it is important that future nutritional treatments optimise patients' health whilst balancing their quality of life. Dietitians will remain key in providing care to these patients as part of the multidisciplinary team, ensuring patients' growth and micronutrient status are optimised.

The future for diet and CD is bright and promising and likely to change over the coming years as further research allows us to learn more about the condition and the impact of specific nutrients.

Instagram: kidsnutritionrd

Website: www.kids-nutrition.com

Hazel Duncan, RD

Paediatric Dietitian, Kids Nutrition

References

- Henderson P, Hansen R, Cameron FL, Gerasimidis K, Rogers P, Bisset WM, Reynish EL, Drummond HE, Anderson NH, Van Limbergen J, Russell RK, Satsangi J, Wilson DC. Rising incidence of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease in Scotland. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012 Jun;18(6):999-1005. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21797. Epub 2011 Jun 17. PMID: 21688352.

- IBD Working Group of the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology HaN: Inflammatory bowel disease in children and adolescents: recommendations for diagnosis – the Porto criteria. J Paediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2005, 41 (1): 1-7

- T Kucharzik and others, on behalf of the European Crohn’s and Colitis Organisation [ECCO], ECCO Guidelines on the Prevention, Diagnosis, and Management of Infections in Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Journal of Crohn's and Colitis, Volume 15, Issue 6, June 2021, Pages 879–913, https://doi.org/10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab052

- Heuschkel RB, Menache CC, Megerian JT, Baird AE. Enteral nutrition and corticosteroids in the treatment of acute Crohn's disease in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2000 Jul;31(1):8-15. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200007000-00005. PMID: 10896064

- Zachos M, Tondeur M, Griffiths AM. Enteral nutritional therapy for induction of remission in Crohn's disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Jan 24;(1):CD000542. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000542.pub2. Update in: Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Apr 01;4:CD000542. PMID: 17253452.

- Bischoff SC, Escher J, Hebuterne X, Klek S, Krnaric Z, Schneider S, Shamir R, Stardelova K, Wierdsma N, Wiskin AE, Forbes A (2000) ESPEN practical guideline: clinical nutrition in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Nutr: 39 (3): 632-653

- Lee D, Baldassano RN, Otley AR, Albenberg L, Griffiths AM, Compher C, Chen EZ, Li H, Gilroy E, Nessal L, Grant A, Chehoud C, Bushman F, Wu G, Lewis JD (2015) Comparative effectiveness of nutritional and biological therapy in North American children with active Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis; 21: 1786-93

- Suskind DL Th specific carnbohydrate diet and diet modification as Induction Therapy doe Paediatric Drohn’s Disease: A randomized Diet Control Trial Nuttrients 2020, 12, 3749; doi: 10.3390/nu12123749

- Levine A; Wine E; Assa A; Boneh RS, Shaoul R, Kori M, Cohen S, Peleg S, Shamaly H; On A et al. Crohn’s disease nExclusion diet plus partial enteral nutrition induces sustained remission in a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology 2019, 157, 440-450,

- Svolos V, Hansen R, Nichols B, Quince C, Ijaz UZ, Papadopoulou RT, Edwards CA, Watson D, Alghamdi A,Brejnrod A, Ansalone C, Duncan H, Gervais L, Tayler R, Salmond J, Bolognini D, Klopfleisch R, Gaya D, Milling S, Russell RK, & Gerasimidis K (2019) Gastroenterology Treatment of Active Crohn’s Disease with an ordinary food-based diet that replicates exclusive enteral nutrition Gastroenterology 2019 156 (5): 1354-1367