WHAT DID 'LOCKDOWN LIFE' MEAN FOR CHILDREN'S NUTRITION?

Posted on

Millions of children have returned to some form of normality this month, after the school gates officially reopened to all pupils. Did they eat well during lockdown? How did being at home for that length of time affect their eating habits? Healthy weight charity, Food Active, has recently researched children’s nutrition during lockdown, with some interesting results. Beth Bradshaw, ANutr reports on the findings.

The COVID-19 outbreak resulted in the first countrywide school shutdown in modern British history and lasted more than 150 days. It was a long time for most of us, more so for little ones who were out of their usual classroom routine, for what must have, to them, seemed like a lifetime!

During the emergency phase of the pandemic, lockdown meant changes for children’s food. Whether it was the types of food eaten, or the time it was consumed, every child’s diet will have been affected in one way or another, with some experiencing greater changes than others.

Food Active’s latest research published last week, with the Children’s Food Campaign, gathered views and experiences from over 750 parents across the UK to explore how ‘lockdown life’ affected children’s eating habits and preferences.1

“MORE TIME TO COOK AND SPACE TO BE CREATIVE”

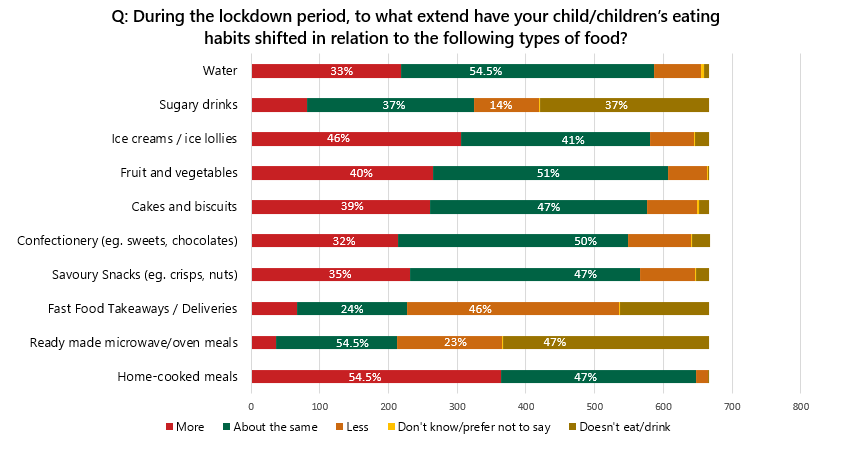

It was evident from the parents we spoke to, that there was an increase in home cooking, attributed to the fact that many parents were working from home. Over half (54.5%) said their children were eating more homemade meals (see Figure 1). This echoes some of the existing research and polling data that has been published over the last six months.2,3 Even without knowing if these changes will be sustained, this is without doubt a change for the better, as food consumed inside the home tends to be lower in calories, fat, sugar and salt compared with food consumed outside the home.4

Almost three in five parents (59%) said their children’s interest in cooking had increased –another promising finding, as there is some evidence to suggest involving children in the preparation of healthy and balanced meals could help to improve their diets and vegetable intake.5

Figure 1: Children’s Food Campaign and Food Active (2020) COVID-19 and Children’s Food: Parents’ Priorities for Building Back Better. https://bit.ly/2FvYAeX

Other positive changes to children’s diets during lockdown included fewer takeaways consumed (46%), sustained or increased water intake (33%) and an increase in fruit and veg consumption (40%). All these are again encouraging findings, when currently only 18% of children aged 5 to 15 in England eat five standard portions of fruit and veg.5

“ALWAYS A BOY IN THE KITCHEN LOOKING FOR FOOD”

Not all new habits were positive, however. Something that was also made very clear by parents was the sheer amount of grazing or snacking their children were doing whilst they were stuck at home all day (I can appreciate that with two teenage boys living at home! – Ed.)

Seventy percent of parents saw a rise in their children’s snacking habits, eating more crisps (35%), ice creams and lollies (46%), cakes and biscuits (40%), sweets and chocolate (30%) [see Figure 1]. Lack of routine, boredom, constant access to food in the house and provision of treats to alleviate pressure, were highlighted as significant factors influencing children’s snacking habits during this period.

This begs the question whether all the positive impacts have been mediated by the onslaught of snacking, reported by a huge number of the parents we surveyed.

The economic impact of COVID-19 has also led to a large rise in food insecurity across the UK, which meant many children struggled to access food at all. The Trussell Trust reported a 107% increase in the number of children needing support from a food bank in April 2020.7 Though the Government introduced replacement support for those entitled to free school meals, reports estimated that 500,000 children eligible for free school meals were at risk of missing out.8 Another study also found fruit and veg intake in children receiving free school meals had significantly decreased.9

“THE COVID-19 LENS”

The results from our survey convey a hugely mixed picture and cannot conclude whether ‘lockdown life’ has had a positive or negative impact on children’s diets overall. It is important to bear in mind that these changes will be felt differently across the social gradient, particularly for vulnerable children or those living in food insecure households.

The medium- to long-term impact on children’s food habits, as they return to the routine of school life, remains to be seen. However, we hope local and national Government can act to capitalise on the positive changes reported, and mitigate the negative, in order to protect children’s health – particularly the most vulnerable.

For more information on the survey and to access the full results, please visit www.foodactive.org.uk

Beth Molly Bradshaw ANutr

Food Active, Health Equalities Group

Beth has has worked at Food Active, a healthy weight charity for over two years and volunteered for a further 18 months. She has a passion for the wider determinants of health and campaigning for an environment that is more conducive to healthy lifestyles and behaviours.

Twitter: @BMBradshaw95

Email: [email protected]

PHOTO: by StockSnap from Pixabay

References

- Children’s Food Campaign and Food Active (2020). COVID-19 and Children’s Food: Parents’ Priorities for Building Back Better [online] Available at: http://www.foodactive.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Childrens_Food_Covid19_Briefing.pdf [Accessed: 10th September 2020]

- Obesity Health Alliance (2020). The Role of Supermarkets in Helping us be Healthy [online] Available at: http://obesityhealthalliance.org.uk/2020/05/06/the-role-of-supermarkets-in-helping-us-be-healthy/ [Accessed: 1st September 2020]

- The Independent (2020). More than a fifth of Brits cooking every meal from scratch during lockdown, Tesco finds [online] Available at: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/coronavirus-lockdown-uk-cooking-habits-tesco-a9468221.html [Accessed: 10th September 2020]

- Public Health England (2020). Health Matters: obesity and the food environment [online] Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-matters-obesity-and-the-food-environment/health-matters-obesity-and-the-food-environment--2 [Accessed: 10th September 2020]

- Horst van der K, Ferrage A and Rytz A (2014). Involving children in meal preparation. Effects on food intake. Appetite. 79; p 18-24

- Health Survey for England (2018). Explore the trends – Fruit and vegetable intake [online] Available at: http://healthsurvey.hscic.gov.uk/data-visualisation/data-visualisation/explore-the-trends/fruit-vegetables.aspx?type=child#:~:text=aged%205%2D15-,In%202018%2C%2018%25%20of%20children%20aged%205%20to%2015%20ate,and%20levels%20of%20physical%20activity. [Accessed: 10th September 2020]

- The Trussell Trust (2020). The Impact of the Covid Crisis on Food Banks [online] Available at: https://www.trusselltrust.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2020/06/APRIL-Data-briefing_external.pdf [Accessed: 10th September 2020]

- The Food Foundation (2020). Hunger strikes during COVID-19: polling data [online] Available at: https://foodfoundation.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Hunger-release-FINAL.pdf [Accessed: 10th September 2020]

- Defeyter G and Mann E (2020). The Free School Meal Voucher Scheme: What are children actually eating and drinking [online] Available at: https://northumbria-cdn.azureedge.net/-/media/corporate-website/new-sitecore-gallery/news/documents/pdf/covid-19-free-school-meal-vouchers-final.pdf?modified=20200605160553 [Accessed: 10th September 2020]