SAPROPTERIN IN PHENYLKETONURIA (PKU) - A CHALLENGING RESULT FOR IMD DIETITIANS by Simon Tapley, RD

Posted on

Every once in a while, a rumour of a drug on the horizon circulates around a patient population offering hope of a meaningful difference in quality of life or a dramatic change in symptoms. More often than not, these rumours fizzle out, chatter subsides and the forums go quiet again until another trial drug hits the headlines and stokes the hope once again.

Fortunately, pharmacology is persistent. Sometimes the rumour becomes reality and the life-changing miracle drug comes to the fore: Insulin in diabetes, statins in hyperlipidaemia, antiretrovirals in HIV. Sapropterin is not quite in that category. It won’t save lives; it won’t work in everyone and it won’t cure the disorder – but it will change the lives of many people with phenylketonuria (PKU).

Fortunately, pharmacology is persistent. Sometimes the rumour becomes reality and the life-changing miracle drug comes to the fore: Insulin in diabetes, statins in hyperlipidaemia, antiretrovirals in HIV. Sapropterin is not quite in that category. It won’t save lives; it won’t work in everyone and it won’t cure the disorder – but it will change the lives of many people with phenylketonuria (PKU).

This is a drug that has teased the patient population in the UK for over a decade, from the trials to the launch in America, to the campaigns for its UK approval and, finally, the biggest tease is the fact that it will be selective in who it helps.

WHAT IS PKU?

WHAT IS PKU?

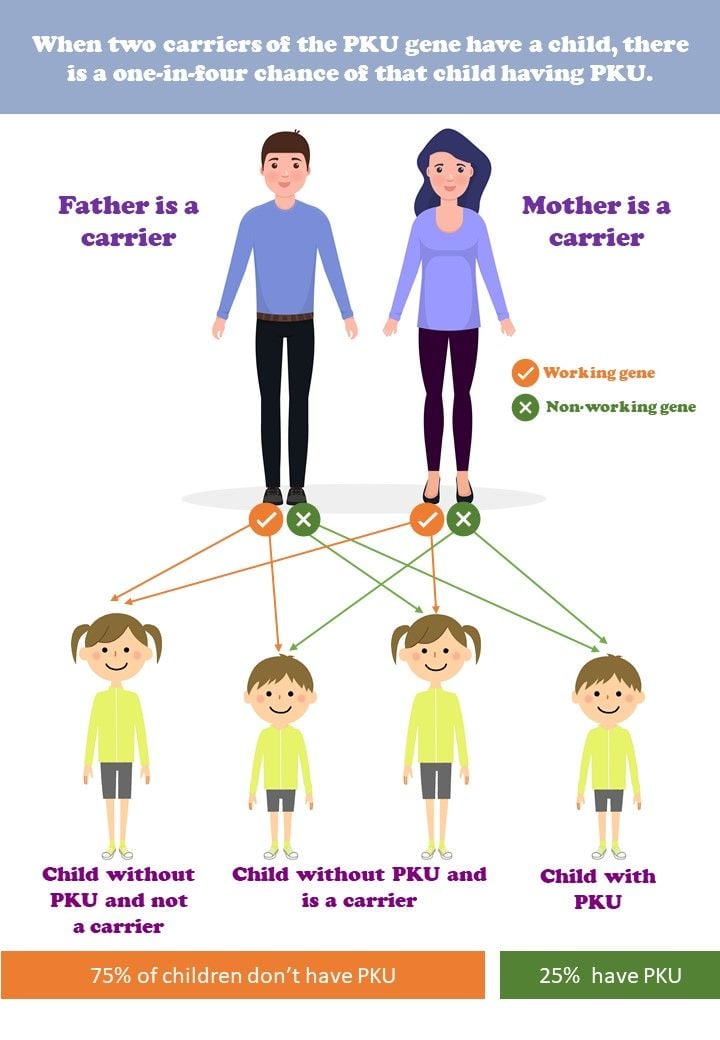

The inherited metabolic disorder (IMD), PKU, is caused by a deficiency in the enzyme phenylalanine hydroxylase (PAH), which converts the aromatic amino acid phenylalanine (Phe) into tyrosine (Tyr). When PAH is deficient, Phe levels can rise causing devastating developmental delay and reduced neurocognitive function in childhood, microcephaly and cardiac complications in utero and a spectrum of more subtle symptoms in adulthood, such as reduced executive function, increased anxiety and depression.1

To reduce Phe levels and prevent these symptoms, treatment has traditionally been synthetic Phe-free protein substitutes alongside a severely restricted low-protein diet, sometimes as low as 3g of natural protein per day. But now, sapropterin is available. It works as a cofactor, a synthetic form of the naturally present tetrahydrobiopterin, that fits into residual PAH hydroxylating Phe into Tyr.

HOW DOES SAPROPTERIN HELP?

The key word here is residual. A cofactor can only affect the enzyme that is present and if that enzyme is very sparse or is misshaped then more of the cofactor will not make a significant difference. Whether or not someone with PKU responds to sapropterin depends on their phenotype. In the situation that a patient has a suitable phenotype, the drug can be effective in lowering Phe levels and allows an increase in natural protein intake. Rarely will it allow people to have an unrestricted diet, but there will be significantly more food choices available for many people.

The National Society for PKU (NSPKU) conducted a survey in the UK with 631 patients with PKU, revealing the average natural protein tolerance was only 10g/day.2 Response to sapropterin could mean an increase to 30g protein/day. This has the potential of allowing people to enjoy food at parties, meals out, at schools or even to grab food on the run whilst maintaining acceptable Phe levels. Sapropterin has the potential to reduce previously uncontrolled Phe levels in pregnancy and childhood, lessening the risk of severely detrimental symptoms of maternal and childhood PKU.

The National Society for PKU (NSPKU) conducted a survey in the UK with 631 patients with PKU, revealing the average natural protein tolerance was only 10g/day.2 Response to sapropterin could mean an increase to 30g protein/day. This has the potential of allowing people to enjoy food at parties, meals out, at schools or even to grab food on the run whilst maintaining acceptable Phe levels. Sapropterin has the potential to reduce previously uncontrolled Phe levels in pregnancy and childhood, lessening the risk of severely detrimental symptoms of maternal and childhood PKU.

UK RECOMMENDATIONS AND ITS USE

In December 2021, NHS England announced that sapropterin would be made available for all patients with PKU.3 Specialist metabolic dietitians are recognised as experts in PKU and funding has been allocated for their important work in the roll out of this drug over the coming year.

Since the December announcement, metabolic dietitians across the country have been busy planning and preparing. We have been working out how best to support the vast majority of the patient population through responsiveness trials with detailed monitoring, dietary adjustment and counselling on the results. Funding for dietetic time is limited to 12 months, generating a huge challenge to get this work done.

The BIMDG has put together a working party to lay down a pathway for identifying patients who respond to the drug. The process includes genetic testing to rule out patients with phenotypes that won’t respond and to put the rest forward for responsiveness testing in a controlled and structured way. Once on the trial, patients can only hope they respond and their prescription continues.4

Simon Tapley, RD

Specialist Adult IMD Dietitian

University Hospitals Bristol and Weston

Simon is working in IMD, having previously specialised in

Gastroenterology and Neurology at Weston General Hospital.

References

- Van Wegberg AMJ, MacDonald A, Ahring K, Bélanger-Quintana A, Blau N, Bosch AM, Burlina A, Campistol J, Feillet F, Giżewska M and Huijbregts SC (2017). The complete European guidelines on phenylketonuria: diagnosis and treatment. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases, 12(1), p 1-56

- Ford S, O'Driscoll M and MacDonald A (2018). Living with Phenylketonuria: Lessons from the PKU community. Molecular Genetics and Metabolism Reports, 17, p 57-63

- https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/12/commissioning-position-on-sapropterin-for-the-treatment-of-phenylketonuria-december-2021.pdf (accessed on18.02.2022)

- https://www.bimdg.org.uk/site/dietitians-sapropterin.asp (accessed on 18.02.2022)