NUTRITION IN MOTOR NEURONE DISEASE by Catriona Lawson, ANutr

Posted on

Motor neurone disease (MND), is a progressive neurodegenerative disease that affects the motor neurons responsible for controlling voluntary muscles. As the disease progresses, individuals with MND gradually lose the ability to move, speak, eat, and breathe. Our NHD guest blogger, Catriona Lawson, ANutr, discusses MND and the nutritional management of the disease.

Many people will remember the Motor Neurone Disease (MND) campaigner Doddie Weir, a former Scottish international rugby player who died from the disease last year at the age of 52. Doddie Weir raised a lot of money for MND research and increased awareness of the disease through his My Name'5 Doddie Foundation.

Motor Neurone Disease (MND) is a group of related disorders characterised by progressive degeneration of upper (corticospinal) and lower (spinal and bulbar) motor neurones. This results in muscle atrophy, paralysis and death.1 Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) is the most common type of MND accounting for over 75% of the total number of MND cases.2 ALS causes muscle weakness and stiffness, overactive reflexes and sometimes a rapid change in emotions. Progressive Bulbar Palsy (PBP) is when MND begins in the speech and swallowing muscles.3

Unfortunately, there is currently no cure for MND and the cause of the disease is not yet fully understood. Care is focused on the management of symptoms and palliation to maintain a quality of life.4 MND results in weakness and wasting to muscles involved in movement, breathing, mobility, swallowing and speech. This affects a person's ability to eat and drink and, therefore, their ability to meet their nutritional needs.5

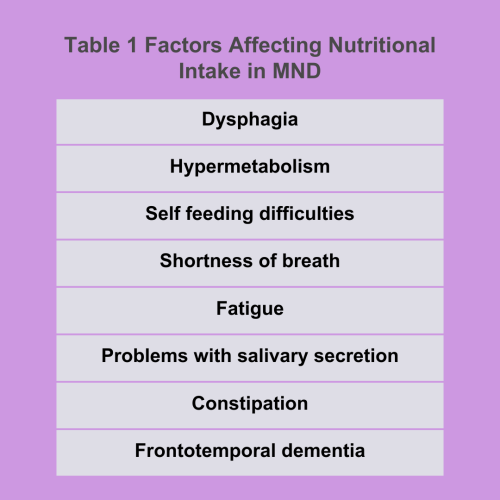

Table 1 shows the factors that can have an impact on nutritional status in MND.

MALNUTRITION IN MND

Malnutrition at the time of diagnosis of MND has been associated with a lower rate of survival.6 Twenty percent of patients with MND will become malnourished, including those without swallowing problems.7 Seventy percent of people with MND have a reduced calorie intake and eat less than the recommended amount for the dietary intake for energy.3

NUTRITIONAL MANAGEMENT OF MND

Nutritional management throughout the progression of MND is vital for quality of life and for optimising the timing of appropriate nutritional interventions. The involvement of a dietitian and a speech and language therapist from the early stage of MND is vital to assess, monitor and review nutritional intake. This is to ensure that practical oral and non-oral dietary advice is given and for nutritional needs to be met.3

Nutritional intake can be optimised by using texture-modified diets, adaptive cutlery, postural support, safe swallowing techniques, food fortification, and increasing the frequency of meals and oral nutritional supplements (ONS). These methods usually become ineffective with the progression of MND, and enteral feeding becomes indicated.8

USE OF GASTROSTOMY FEEDING IN MND

The most common method of artificial nutrition and hydration (ANH) is gastrostomy, either percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) or percutaneous radiological gastrostomy (PRG). When used correctly, gastrostomy can decrease distressed episodes associated with eating and drinking, i.e. choking fears, and it increases nutrition and hydration and decreases social isolation caused by prolonged mealtimes.3 Current evidence shows that PEG or PRG can be inserted at any time during MND. However, the nutritional benefits are reduced as patients enter the terminal phase of MND.9

Pre- gastrostomy assessment should consider the following:

- Respiratory function – patients with failed respiratory function require acclimatisation to Non-Invasive Positive Pressure Ventilation (NIPPV) prior to gastrostomy.

- Stage of MND – patients in the terminal phase of the disease are not likely to benefit from gastrostomy.

- Malnutrition – MND patients with severe malnutrition may benefit from nasogastric (NG) feeding.

- Quality of Life – gastrostomy may reduce the quality of life for both the patient and carer by increasing the burden. However, gastrostomy may also increase the patient’s and carer’s quality of life by decreasing the amount of time eating and reducing the symptoms of dysphagia.9

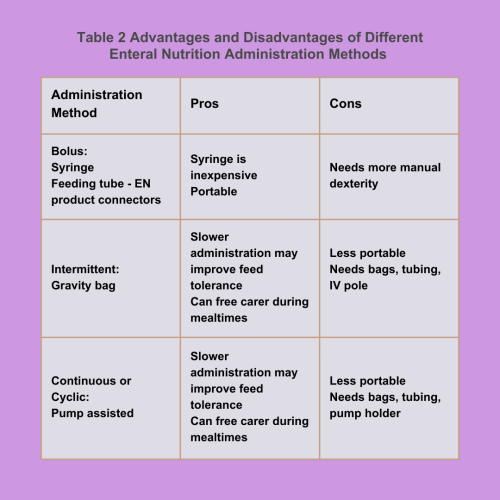

Table 2 shows the advantages and disadvantages of different enteral nutrition administration methods (adapted from Nutritional Care of the Patient with ALS, 2022).10

CONCLUSION

MND is a progressive neurological disorder, resulting in weakness and wasting to muscles involved in movement, breathing, mobility, swallowing and speech. There is currently no cure for the disorder. Patients with MND have a high nutritional risk. Nutritional management throughout the progression of MND is essential for patients’ quality of life and for optimising the timing of appropriate nutritional interventions. Gastronomy (either PEG or PRG) is recommended for long-term nutritional support for patients with MND.

Catriona Lawson, ANutr

Catriona is a freelance nutritionist and has worked as

a dietetic support worker in an acute adult dietetics department within NHS.

She has also worked in a care home as a nutritionist for the elderly with dementia.

Twitter@: @CatrionaLawson1

Website: www.catrionanutritionblog.com

References

- Hardiman O, van den Berg LH and Kiernan MC (2011). Clinical diagnosis and management of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature Reviews Neurology, 7 639-649

- Hobson E, Harwood C, McDermott C, Shaw P (2016). Clinical aspects of motor neurone disease. Spinal cord, nerve, muscle. Medicine 44:9: 552-556

- Williams L (2019). Motor Neurone Disease: Nutritional Management. NHD Magazine

- Daniel I, Greenwood BA (2013). Nutritional management of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nutrition in Clinical Practice 28(3); 392-399

- Desport JC, Preux PM, Truong CT, Courat L, Vallat JM, Couratier P (2000). Nutritional assessment and survival in ALS patients. Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Other Motor Neuron Disorders; 1(2): 91-6

- Limousin N, Blasco H, Corcia P, et al. (2010). Malnutrition at the time of diagnosis is associated with a shorter disease duration in ALS. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 297(1-2):36-39. DOI: 10.1016/j.jns.2010.06.028

- Worwood AM, Leigh PN (1998). Indicators and prevalence of malnutrition in motor neurone disease. European neurology, 40(3), 159–163. https://doi.org/10.1159/000007973

- Miller RG, Jackson CE, Kasarskis EJ et al (2009). Practice parameter update: the care of the patient with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: drug, nutritional, and respiratory therapies (an evidence-based review): report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology; 73: 1218-26

- Cawadias E and Rio A (2019). Motor neurone disease. In Manual of Dietetic Practice, 6th edition. Edited by Joan Gandy (2019) The British Dietetic Association

- Dobak S (2022). Nutritional Care of the Patient with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Practical Gastroenterology. 46. 60-67